Nicole Harris will tell you what she thinks. Confident in her opinions but open to every offered lesson, Harris is comfortable speaking her mind. Someone who takes life one day at a time, Harris operates with a focused-on-the-next-opportunity mindset instead of dwelling on what did not come her way. This capacity to be optimistic and forward focused has guided Harris through adversity, while allowing her to appreciate how far she has come—and how far she can throw.

Born and raised in Sydney, Australia, Harris has found success on and off the field of play. A seasoned athlete and proven competitor, Harris has made her mark at three Special Olympics World Games. Harris earned her spot on the basketball court at the World Games Athens 2011 and World Games Los Angeles 2015. In between, Harris featured in the World Winter Games Pyeongchang 2013 in alpine skiing.

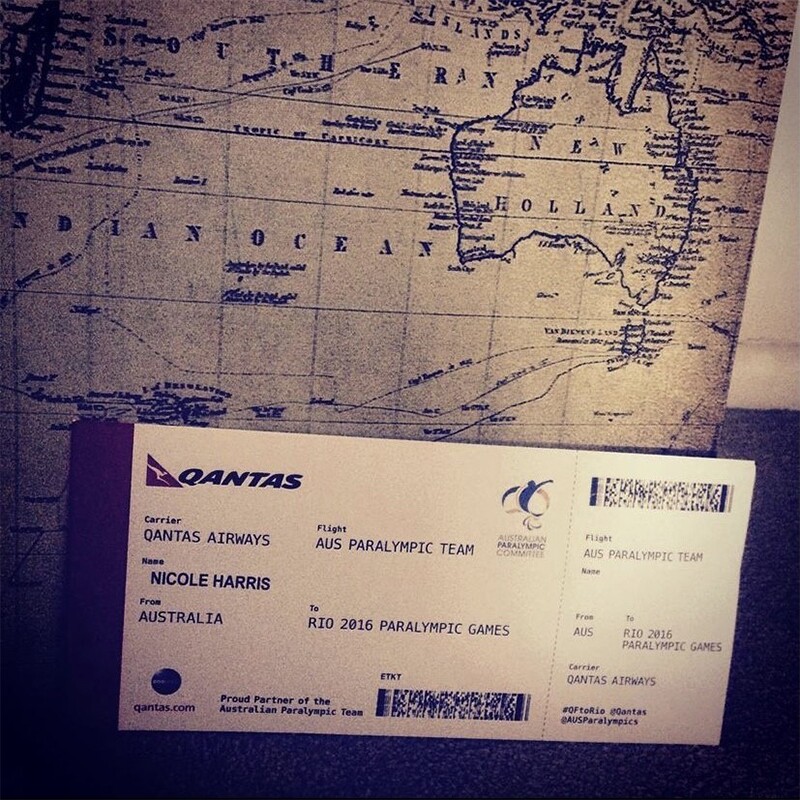

An Australian Paralympic Emerging Talent coach noticed Harris in 2012 at a meet in Sydney. They believed that Harris, who was competing in distance running at the time, was well suited for throwing apparatuses because of her long limbs. Harris gave it a shot and, in 2013, emerged on the international athletics stage. Three years and lots of hours spent in transit to and from trainings later, Harris made her Paralympics debut at the 2016 Rio Games, placing seventh overall in the F20 shot put event.

While gearing up to qualify for the Tokyo Games, Harris’ training was hampered by a series of ill-timed injuries. 2019 became a year of physical pain and perpetual setback for the then twenty-seven-year-old. Most challenging, however, was the absence of selfhood Harris experienced during this period. Harris sought inspiration from the resilience and support of her ‘base’—made up of family, close friends and role models—to help her navigate the mental and physical trials of injury.

Feeling “ok” now, Harris is keeping a gentle, unassuming gaze on Paris 2024. For now, she is just focused on the day before her. Amidst another lockdown in her home country, Harris is taking time each day to check in on her friends and improve upon her weaknesses. In a period of great uncertainty across the globe, Harris is generating momentum by asking one question at a time.

INTERVIEWER

You describe yourself as someone who is comfortable asking questions. What do you think makes a good question?

HARRIS

The way I’ve been brought up in my family is to always ask questions—you’re never going to get anywhere in life without asking questions. Asking questions can take you down different paths and help get more information out of people to see what they actually want to know about you. My interpretation of a good question is fully understanding the topics that lead to endless discussion within a group about the question.

INTERVIEWER

How has asking the right questions helped you navigate your career as an athlete?

HARRIS

Asking the right questions helps make a better experience for every athlete. In most of my individual sports, you’ve got to ask questions to become a better athlete—especially when you’re training and going to competition. Also taking on that feedback. In my past experiences at World Games, asking questions to get feedback from my coaches has been very important. Being more open to asking those questions and getting that feedback has been beneficial.

INTERVIEWER

Does anybody stick out as a particularly influential person in your sporting career?

HARRIS

My physical education teacher at school, Robyn, was one my main mentors. I met Robyn in Year 8. I finished school in 2010, so that was a while ago now—pretty scary! She was actually my coach in long-distance running which I did before I started shot put, and just a mentor and a friend along the way.

The earliest memory I have of her is going to afternoon school fitness sessions that she ran. She used to come out on Friday nights, and we had trainings on the track where the Olympics were. She’s always motivated me to be the best version of myself, always pushed me in my sporting endeavors and dreams, and always encouraged me to start a career in fitness. She was a runner herself, so being a 1500-meter coach for me was very helpful.

INTERVIEWER

What memories come to mind when thinking about Robyn?

HARRIS

One of the best memories I have with her is sharing the experience of winning the gold medal at the 2012 Australia National Championships. Getting an Australian record for classification at that, as well. It was pretty cool to experience that with her and know all of the training we did together because she used to actually run with me during our training sessions, so we experienced all our pain together!

INTERVIEWER

In that gold medal moment, do you remember what you said to her? Or what she said to you?

HARRIS

I think we were just so excited; I don’t think it had really sunk it. We were both just so excited because all the hard work we put in planned out. I don’t know. I’m one of those people who works on adrenaline, so I never really know what I’ve done until a few hours later. Then it’s like: oh my god, I actually just won.

INTERVIEWER

When that adrenaline settles, do you find yourself being able to relive the moment and celebrate what you might have missed?

HARRIS

I think so! I mean every time you win something like that—I like to be modest but I have won a few medals, or a lot—there is adrenaline! As a child I didn’t win many races. So to actually win a few medals, I think, at first, I was more surprised for myself. Like: is this actually happening? And then it’s the adrenaline of the actual moment coming back around.

INTERVIEWER

As a child you didn’t win very much?

HARRIS

I did athletics when I was young but was never really competitive. It didn’t happen until high school that I was competitive. It hit then. I was in the right training. I never really had a coach until I was in high school, so I guess that was part of it too. I found great mentors who got me into a program based around my sport.

Robyn and another physical education teacher at my school, who were kind of learning as they coached me, since they never had a student with ID participate in sport. There were students with ID at the school, but nobody actually participated in sport yet. It was a learning curve for all of us—them, me, and my parents.

INTERVIEWER

Are you someone who is, at least somewhat, comfortable changing directions? When you were invited to try out shot put, was that something you took in stride?

HARRIS

I’m not usually someone who likes changing directions. Mostly because I kind of fear the unknown. When the Australian Paralympic Emerging Talent Coaches came up to me after I finished my 2012 gold medal race, I was already on cloud nine from my win. The coach came up to me in the stands and asked if I wanted to try shot put because I have long limbs and I’m tall. They said I’d have a really good chance to make Rio or the next one—Tokyo—and put me on to the coaches.

Being in that environment was really cool, I had never been in a big training group before. Everyone there kind of did hammer throw, discus and shot put. It was probably a two-hour drive, to training and back again. I usually spent four hours at training, so it was thirty plus hours a week—training, driving out there, driving back home. The first year I went out, I was just getting my provisional driver’s license. After I got my provisional driver’s license, I ended up driving out there by myself all the time.

INTERVIEWER

Was that challenging, having so much of your day consumed by sport?

HARRIS

I guess I didn’t really take it into that much consideration because I had a really good training squad. They were so supportive and kind of turned into my family. You kind of didn’t think about travel time until you were going home. Then it was like: wow, I’ve been here for so long already.

INTERVIEWER

What was the training itself like?

HARRIS

We pretty much threw for nearly two hours to start with, everyone had a set amount of throws they did in the training session. Then you did an hour and a half of gym that was based around your disability. I have an intellectual disability, but I also have mild cerebral palsy. So they pretty much based my training program and weight sessions around that.

INTERVIEWER

Where are you in your sporting career now?

HARRIS

That chapter hasn’t really closed yet. I’ve been injured multiple times over my career. Overcoming all of the injuries and getting through all of the rehab, I think it just makes you a stronger athlete. I really haven’t closed my sporting-career chapter yet.

I’ve done my back, my ankles; I’ve had concussions. In 2019, I ended up doing my hamstring in a shot put competition. It was a local competition during ski season, so I had been skiing all week. It was in July, right at the end of my birthday week. So that was fun!

I was going for a throw and over rotated and was trying to get past the midline so I wouldn’t foul. There was a discus cage around from the night before. As my heel went outside the shot put circle, my heel got stuck. They were like: ‘you haven’t teared it!’ And I was like: ok, sounds good but it’s really sore and I can’t really walk—I’ve definitely done my hamstring.

Two weeks later I was walking down the stairs at home and my knee went forward awkwardly. I ended up doing both my sciatic nerves in my back. So that wasn’t the greatest time in my sporting career.

INTERVIEWER

How did those injuries change the narrative of this chapter of your career?

HARRIS

This was when I was trying to qualify for Tokyo, when Tokyo was supposed to be in 2020. For the sciatic nerve injuries, from August to February, I had six cortisone injections. One of them being a nerve block injection.

It was a struggle. I was on so much pain medication, it was like I wasn’t really here, I guess. I wasn’t really myself. I was just trying to get through the pain. It was also annoying because every specialist you go to tells you something different.”

INTERVIEWER

How are you feeling now?

HARRIS

I’m feeling ok now. Every now and then it comes back—loss of sensation, like nerve pain, comes back. I’m trying to get through it with Pilates and rehab exercises that focus on my weaknesses. I’m not sure about the next Paralympics, it’s not out of the cards, but I’d say it’s probably fifty/fifty, because it’s another three or four years. So, I don’t right now, but I have a really strong base behind me.

INTERVIEWER

How, if at all, did this period of hardship change your mindset?

HARRIS

Every day I’m just thankful to my alive. All my friends, they are the type who have a five-year plan. I’m not one of those types of people. I’m like: yeah, I’ll wing it. If an opportunity comes up, that’s great. If an opportunity doesn’t come up, that’s ok because I know another one is coming.

A lot of my resilience comes from learning from the people around me; how they live their life, how they choose to mentor people. Some sporting celebrities—Lindsey Vonn and her resilience, Bethany Hamilton and her resilience—the injuries they’ve overcome, and how they live their life. I gain perspective from them.

INTERVIEWER

How has focusing on future opportunity instead of missed opportunity helped you through the pandemic?

HARRIS

Covid has really brought back, I think, more about family and friends and keeping in touch with people. I think it’s more or so about checking up on people, seeing how they are. Everyone’s in the same boat. No one is really peaking right now; we are all just trying to make the most of each day.

I’ve got a bubbly personality, I’m really open. Probably the worst thing is that I tend to tell people what I think, and I feel like it’s not a great trait, but it gets me out of difficult situations where people try to just step over you.

INTERVIEWER

What have you learned from these moments where people try to step over you?

HARRIS

There’s been a few coaches in the past who, I don’t know, like treated you in a different way. Like you’re, I know it sounds crappy, but not as smart as you are. So it’s about showing people like that you’re a person. And you’re actually not dumb at all, that you do know what you’re talking about. Then they step back and have the realization: she does know what she is talking about. I think you need to stand up for yourself in that way. I think that’s taught me a lot in general life as well—to stand up for what I believe in.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of beliefs, what are you cheering for most? What do you believe is next for the Special Olympics movement?

HARRIS

A cheer would be seeing more athletes getting involved in the Special Olympics movement. Not many children with intellectual disabilities know about Special Olympics. I didn’t until I was sixteen or seventeen. Also, making the athletes experience better every year and creating memories with all your teammates through every Games experience. Making memories helps bring more people on and shows the world what we are achieving.